Principal Component Analysis Covariance Matrix

You tend to use the covariance matrix when the variable scales are similar and the correlation matrix when variables are on different scales.Using the correlation matrix is equivalent to standardizing each of the variables (to mean 0 and standard deviation 1). In general, PCA with and without standardizing will give different results. Especially when the scales are different.As an example, take a look at this R heptathlon data set. Some of the variables have an average value of about 1.8 (the high jump), whereas other variables (run 800m) are around 120. Bernard Flury, in his excellent book introducing multivariate analysis, described this as an anti-property of principal components.

It's actually worse than choosing between correlation or covariance. If you changed the units (e.g. US style gallons, inches etc. And EU style litres, centimetres) you will get substantively different projections of the data.The argument against automatically using correlation matrices is that it is quite a brutal way of standardising your data.

The problem with automatically using the covariance matrix, which is very apparent with that heptathalon data, is that the variables with the highest variance will dominate the first principal component (the variance maximising property).So the 'best' method to use is based on a subjective choice, careful thought and some experience. $begingroup$ This is by far the most sensible answer here, as it actually gives a proper view that covariance wins when appropriate. Too many answers here and elsewhere mention the usual 'it depends' without actually giving a hard basis for why one should prefer covariance if possible.

Here lep does: covariance doesn't chuck out any of the info which correlation does. The stock data example is a good one: high beta stocks will of course have higher loadings but they probably should, just like any facet of any analysis that is more volatile is usually more interesting (within reason). $endgroup$–Nov 12 '14 at 15:27. A common answer is to suggest that covariance is used when variables are on the same scale, and correlation when their scales are different. However, this is only true when scale of the variables isn't a factor.

Otherwise, why would anyone ever do covariance PCA? It would be safer to always perform correlation PCA.Imagine that your variables have different units of measure, such as meters and kilograms. It shouldn't matter whether you use meters or centimeters in this case, so you could argue that correlation matrix should be used.Consider now population of people in different states.

The units of measure are the same - counts (number) of people. Now, the scales could be different: DC has 600K and CA - 38M people. Should we use correlation matrix here? In some applications we do want to adjust for the size of the state.

Using the covariance matrix is one way for building factors that account for the size of the state.Hence, my answer is to use covariance matrix when variance of the original variable is important, and use correlation when it is not. I personally find it very valuable to discuss these options in light of the maximum-likelihood principal component analysis model (MLPCA) 1,2. In MLPCA one applies a scaling (or even a rotation) such that the measurement errors in the measured variables are independent and distributed according to the standard normal distribution.

This scaling is also known as maximum likelihood scaling (MALS) 3. In some case, the PCA model and the parameter defining the MALS scaling/rotation can be estimated together 4.To interpret correlation-based and covariance-based PCA, one can then argue that:. Covariance-based PCA is equivalent to MLPCA whenever the variance-covariance matrix of the measurement errors is assumed diagonal with equal elements on its diagonal. The measurement error variance parameter can then be estimated by applying the probabilistic principal component analysis (PPCA) model 5. I find this a reasonable assumption in several cases I have studied, specifically when all measurements are of the same type of variable (e.g. All flows, all temperatures, all concentrations, or all absorbance measurements).

Indeed, it can be safe to assume that the measurement errors for such variables are distributed independently and identically. Correlation-based PCA is equivalent to MLPCA whenever the variance-covariance matrix of the measurement errors is assumed diagonal with each element on the diagonal proportional to the overall variance of the corresponding measured variable. While this is a popular method, I personally find the proportionality assumption unreasonable in most cases I study. As a consequence, this means I cannot interpret correlation-based PCA as an MLPCA model.

In the cases where (1) the implied assumptions of covariance-based PCA do not apply and (2) an MLPCA interpretation is valuable, I recommend to use one of the MLPCA methods instead 1-4. Correlation-based and covariance-based PCA will produce the exact same results -apart from a scalar multiplier- when the individual variances for each variable are all exactly equal to each other.

When these individual variances are similar but not the same, both methods will produce similar results.As stressed above already, the ultimate choice depends on the assumptions you are making. In addition, the utility of any particular model depends also on the context and purpose of your analysis. To quote George E. Box: 'All models are wrong, but some are useful'.1 Wentzell, P. D., Andrews, D.

T., Hamilton, D. C., Faber, K., & Kowalski, B. Maximum likelihood principal component analysis. Journal of Chemometrics, 11(4), 339-366.2 Wentzell, P.

D., & Lohnes, M. Maximum likelihood principal component analysis with correlated measurement errors: theoretical and practical considerations. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 45(1-2), 65-85.3 Hoefsloot, H. C., Verouden, M.

P., Westerhuis, J. A., & Smilde, A.

Maximum likelihood scaling (MALS). Journal of Chemometrics, 20(3‐4), 120-127.4 Narasimhan, S., & Shah, S. Model identification and error covariance matrix estimation from noisy data using PCA. Control Engineering Practice, 16(1), 146-155.5 Tipping, M. E., & Bishop, C.

Probabilistic principal component analysis. Blood bowl rotspawn model. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology), 61(3), 611-622. The arguments based on scale (for variables expressed in the same physical units) seem rather weak. Imagine a set of (dimensionless) variables whose standard deviations vary between 0.001 and 0.1.

Compared to a standardized value of 1, these both seem to be 'small' and comparable levels of fluctuations. However, when you express them in decibel, this gives a range of -60 dB against -10 and 0 dB, respectively.

Then this would probably then be classified as a 'large range' - especially if you would include a standard deviation close to 0, i.e., minus infinity dB.My suggestion would be to do BOTH a correlation- and covariance-based PCA. If the two give the same (or very similar, whatever this may mean) PCs, then you can be reassured you've got an answer that is meaningul.

Analysis Of Covariance Example

If they give widely different PCs don't use PCA, because two different answers to one problem is not sensible way to solve questions. $begingroup$ (-1) Getting 'two different answers to the same problem' often just means you're bashing away mindlessly without thinking about which technique is appropriate for your analytical aims. It does not mean that one or (as you state) both techniques are not sensible, but only that at least one might not be appropriate for the problem or the data. Furthermore, in many cases you can anticipate that covariance-based PCA and correlation-based PCA should give different answers. After all, they are measuring different aspects of the data. Doing both by default would not make sense.

$endgroup$–Jun 27 '13 at 15:00.

If I have a covariance matrix for a data set and I multiply it times one of it's eigenvectors. Let's say the eigenvector with the highest eigenvalue.

The result is the eigenvector or a scaled version of the eigenvector.What does this really tell me? Why is this the principal component? What property makes it a principal component? Geometrically, I understand that the principal component (eigenvector) will be sloped at the general slope of the data (loosely speaking). Again, can someone help understand why this happens?

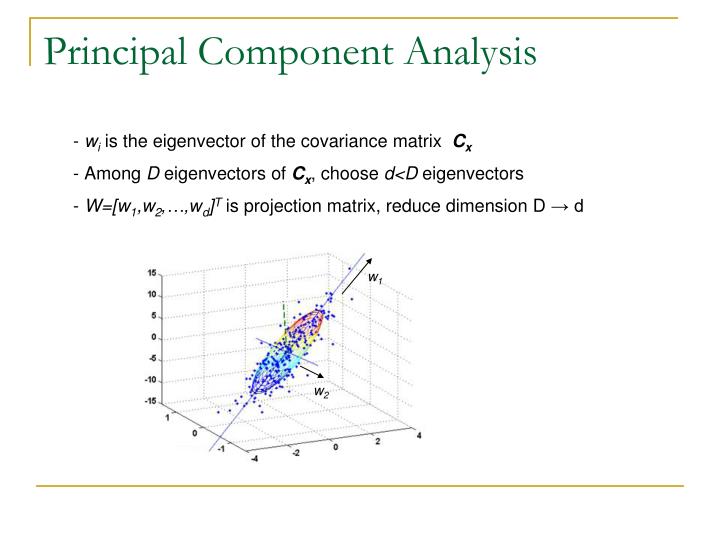

Short answer: The eigenvector with the largest eigenvalue is the direction along which the data set has the maximum variance. Meditate upon this.Long answer: Let's say you want to reduce the dimensionality of your data set, say down to just one dimension. In general, this means picking a unit vector $u$, and replacing each data point, $xi$, with its projection along this vector, $u^T xi$.

Principal Component Analysis Covariance Matrix Function

Of course, you should choose $u$ so that you retain as much of the variation of the data points as possible: if your data points lay along a line and you picked $u$ orthogonal to that line, all the data points would project onto the same value, and you would lose almost all the information in the data set! So you would like to maximize the variance of the new data values $u^T xi$. It's not hard to show that if the covariance matrix of the original data points $xi$ was $Sigma$, the variance of the new data points is just $u^T Sigma u$. As $Sigma$ is symmetric, the unit vector $u$ which maximizes $u^T Sigma u$ is nothing but the eigenvector with the largest eigenvalue.If you want to retain more than one dimension of your data set, in principle what you can do is first find the largest principal component, call it $u1$, then subtract that out from all the data points to get a 'flattened' data set that has no variance along $u1$. Find the principal component of this flattened data set, call it $u2$.

If you stopped here, $u1$ and $u2$ would be a basis of the two-dimensional subspace which retains the most variance of the original data; or, you can repeat the process and get as many dimensions as you want. As it turns out, all the vectors $u1, u2, ldots$ you get from this process are just the eigenvectors of $Sigma$ in decreasing order of eigenvalue. That's why these are the principal components of the data set. Some informal explanation:Covariance matrix $Cy$ (it is symmetric) encodes the correlations between variables of a vector. In general a covariance matrix is non-diagonal (i.e. Have non zero correlations with respect to different variables).But it's interesting to ask, is it possible to diagonalize the covariance matrix by changing basis of the vector? In this case there will be no (i.e.

Zero) correlations between different variables of the vector.Diagonalization of this symmetric matrix is possible with eigen value decomposition.You may read (pages 6-7), by Jonathon Shlens, to get a good understanding.